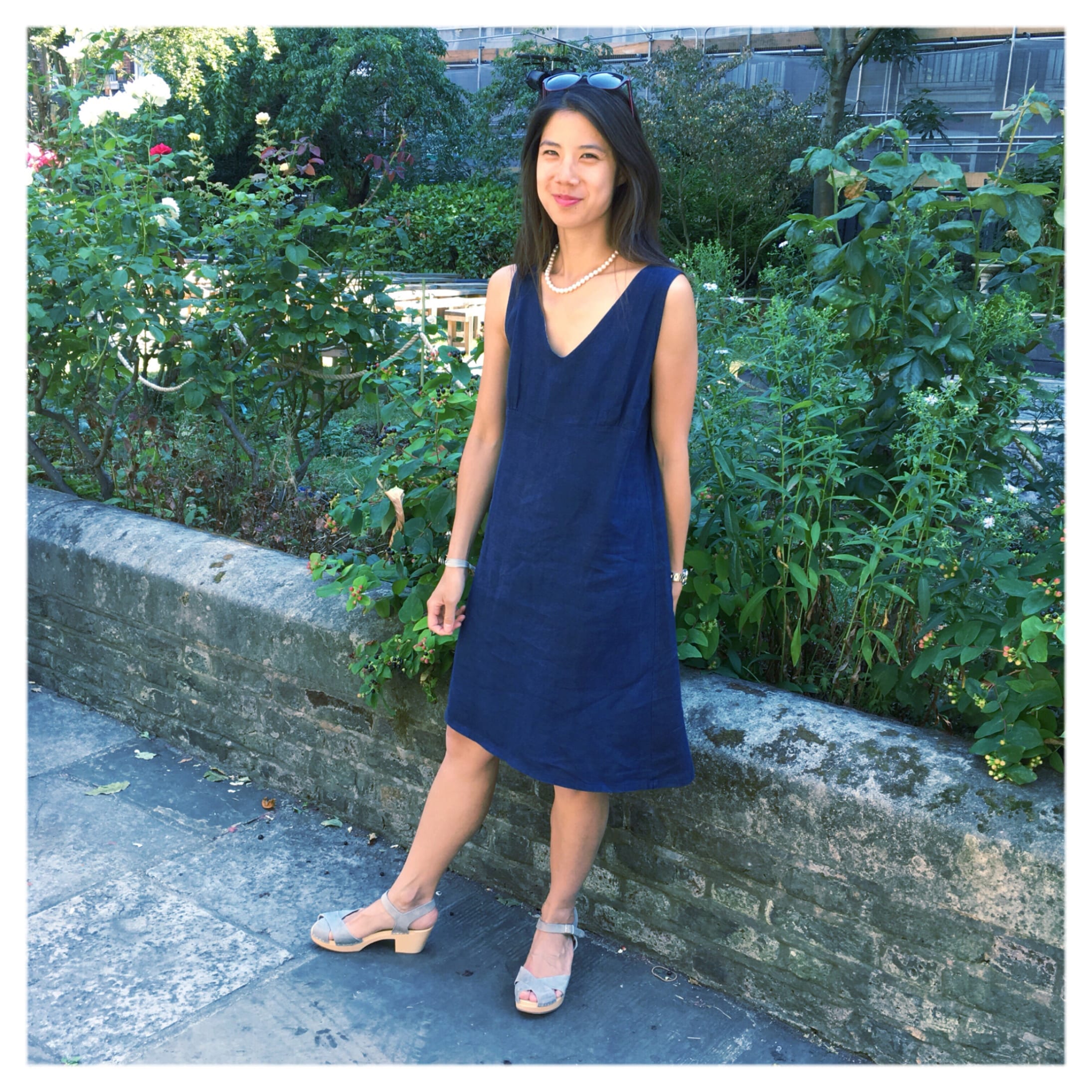

Of all the sustainability topics out there, the issue of greenwashing is pretty problematic. Organic textiles – especially organic cotton – if certified GOTS, is one of those textiles widely accepted as being “sustainable”. Does that mean it’s better? For me, the social issue around labour is the most important and undoubtedly there are good things about GOTS (for an intro into organic, see my blog post here). When it comes to the environmental angle, there is more than one side of the story. I collated a list of myths I’ve read recently in marketing and Dr Grace Peng did the mythbusting for me.

Scroll to the bottom to read about Grace and why it’s worth listening to her. In this world that is littered with misinformation, I hope it gets you thinking twice about the marketing that you read. The interview is long but I promise it’s a good one!

1. Organic cotton is softer

Cotton is made up of sugars linked together into polymer chains, cellulose. Link the sugars one way, and they are carbohydrates, that we can eat for sustenance. Link them another way, and they become cellulose, which is indigestible to humans.

Longer chains of cellulose are softer. How do you get longer chains? More sunlight and cool nights. This is why cotton is largely grown in arid climates, with predictably hot days and cool nights. Nothing to do with organic.

2. Organic cotton is more eco friendly because it’s 80% rainfed

Rain, at the wrong part of the growing/harvest cycle, is bad for cotton. So cotton is often grown in places where you can count on no rain. It is a crop that takes lots of water which needs to be applied just at the right time, with no rain at random times to mess up your planting and harvest. This is a recipe for water scarcity.

The places where organic cotton’s water needs can be met by rainfall alone is minuscule compared to the places where drought-tolerant GMO cotton can be grown. (GMO cotton is engineered to use less water).

3. Organic contains no nasty chemicals and is pesticide free

Organics use pesticides. Sometimes really nasty ones. But, they are “natural pesticides”. When most organizations test for pesticides, they test only for the ones forbidden by organic standards, the newer synthetic ones.

As an aside, this is also the case in food … I read a paper involving testing for both organic and conventional pesticides. The conclusion was that organic kale had the highest pesticide residue! Kale is a brassica, which means cabbage worms love it. Bt kale resists cabbage worm, but organic kale does not. (see Grace’s blog post on it here)

It’s absolutely crazy that one copper salt is “organic” while another one is “synthetic”, and therefore, not organic. However, they both poison the soil with heavy metals.

Also, growing organic pesticides in another field, grinding it up and applying it is a lot of work… the only difference between the organic and manufactured version of the same pesticide is more land, water and labour. Read here about neem oil which is an allowable plant based pesticide.

4. GMO is not “natural”

Organic was a good-hearted effort begun in the 1970s. But technology has changed so much, and organic is not the best land stewardship anymore. GMOs are not allowed in organic agriculture. Organic gives up all the gains in water savings, innate pest resistance, longer staple length to meet an ideal from 50 years ago.

Organic cotton is sprayed with Bt, which is derived from a bacteria that lives in soil. Instead of spraying the bacterium on the crop, as they do in organic agriculture, the gene is spliced into the crop. The GMO bit is adding the Bt to it. Read more here.

Yes, bollworm is just one pest and should be used in conjunction with crop rotation and other IPM, (integrated pest management techniques). With GMO Bt cotton, you really can produce cotton with less water, land and pesticides. 97% fewer pesticides is the norm in both the US and Australia.

But Grace, what about the True Cost documentary highlighting the plight of farmers in India?

Monsanto’s business practices is a different issue from Bt or GMOs in general. I will not defend Monsanto’s business practices, but I will defend science and evidence. The good news is that gene splicing does not have to be done by for-profit companies.

Brazilian scientists produced Bt cotton independently, which they will presumably allow their own farmers to use without charge. Farmers will then be able to save seeds and use it without paying patent royalties. The Gates Foundation is doing something similar but will release it to farmers all over the world.

Bt provides resistance from the most common pests. Farmers don’t want to spray pesticides. It’s bad for the land, bad for themselves, and costs money.

Notes on herbicides and GMO

Monsanto sells Bt cotton with or without Round-up (glyphosate) resistance. So Monsanto makes money selling you the seed and the Round-up. Over-use of glyphosate is creating super-weeds. It’s like over-use of antibiotics breeding super-germs. Monsanto says that they sell Bt cotton with our without the gene for glyphosate resistance. 85% with, 15% without. Farmers can buy the resistant seeds and hope that weeds are not enough of a problem in that field, in that year, that they need to use it. It’s an insurance policy.

The US cotton industry says that it’s 1% organic, 15-16% cleaner cotton, and the rest conventional. Worldwide, the cleaner cotton portion keeps growing, which I suspect is why the Australian numbers look so good compared to 30 years ago.

Spraying so much glyphosate is really bad. But, I have a friend who is a farmer, who says that one application per year, applied at just the time when weeds are taking off, makes a big difference in his yield. Super-weeds are not a problem for him because the glyphosate cuts down the weeds just enough to reduce the work required to deal with the remaining weeds using mechanical means (hoeing or pulling). Weeds compete with the crops for water, nitrogen, etc. So they really do reduce crop yield.

5. Organic cotton is biodegradable, conventional cotton is not.

Any cotton, along with linen, hemp, and some rayons, is just cellulose. You can compost it. But, landfill is problematic. Landfills have been excavated and found banana peels that haven’t degraded!

Also, the dyes and finishes and synthetic thread are contaminants. Microfibers in sewage is a whole other subject. In southern California, SoCal, we recycle our water as much as possible. So our water treatment will remove suspended microfibers. In northern California, where water is more abundant, they just minimally treat the water for disinfection and dump that into the bay. They have microfibers in their bay, which eventually flush into the ocean. But, that’s a sewage treatment problem that is easily fixable. Just add money and infrastructure. SoCal had to do it because water is so scarce here. Other places can do it if they want to.

Note from Kate: blogpost here on how landfills work, and this one here on microfibres. Bear in mind there are also cotton and linen microfibres the ocean that haven’t degraded.

—

OK, so that’s some pretty good myth-busting and logical arguments there… bottom line is that you need to do your own reading and form an opinion. PS. if you need an intro into organic, check out my blog post here. It’s from 2017, but still relevant.

Kate xx

—

Grace Peng …scientist, mom, sewist, lifelong slayer of BS. Her background is in mathematics, chemistry and she holds a PhD in Chemical Physics from the U of Colorado at Boulder and the Joint Institute for Laboratory Astrophysics. Since then, she has been paid to work at the intersection of environmental science, environmental policy, data analysis, data management and software engineering. She has not been paid to be a mother, daughter, wife, and community volunteer, but she works plenty hard at those jobs, too.

PIN FOR LATER: