How to Sew Sustainably is the latest offering in Wendy Ward’s sewing books – there are four other ones focussed on dressmaking. There are many ways one can try to sew ‘sustainably’ … the branch that Wendy’s book belongs to is the “waste nothing and reuse everything” one. (As an aside, if you’re keen to read about what happens to discarded textiles, you can read some of my posts on that here). So it follows that the book is primarily giving ideas for reusing, upcycling textiles in different ways with the use of a sewing machine. Whilst there are garment projects, it is not a typical dressmaking pattern book with pull out sheets that you trace.

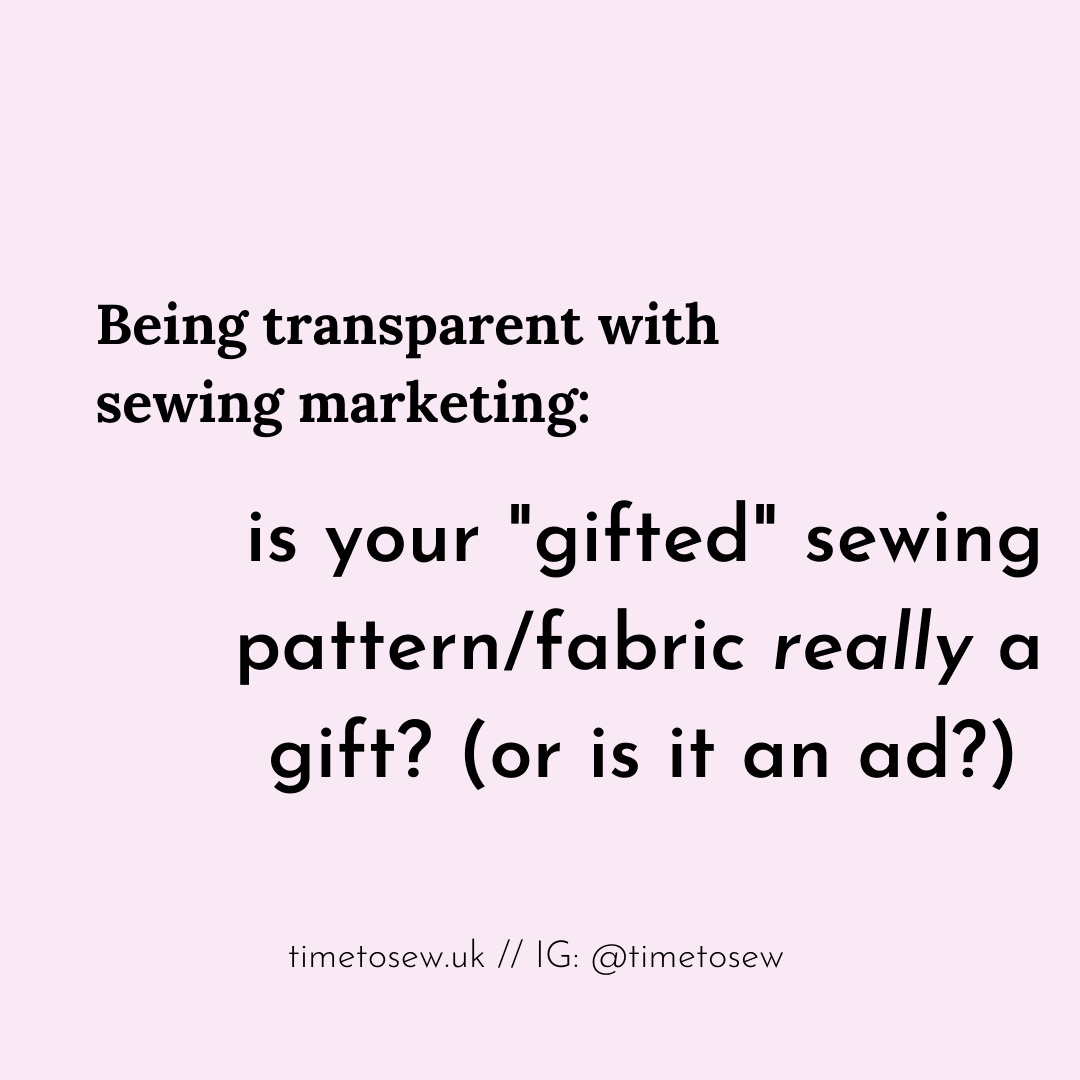

Disclaimer: this book was given to me as a PR product. I could tell you that everything in it is my opinion etc. – which it is – but seeing as I do know Wendy and I fully believe in her passion for all things sustainable fashion, I do have bias. However, I will do my best to give you a balanced view of why you would (or not) want the book. Note: no affiliate links.

A note on ‘quality’. In this day and age where anyone can put anything on the internet, it can be hard to tell who is the real deal and who is just about pretty pictures. I like that Wendy is a fashion professional and I have trust in her patternmaking skills!

Contents

As you can see here, as well as the projects, Wendy gives a lot of sewing tips. I particularly enjoyed reading this section. Making continuous bias binding from one square of fabric is one of my favourite techniques. I also like that she has tips for denim and leather, down to the stitch length and needle size, when to use what kind of hem. This is all really useful stuff, especially if you just need a starting point to experiment with your machine settings. Otherwise it can be a lot of time spent going through tons of internet material to figure out what to do. There’s quite a few pages on mending as well.

The projects

For difficulty, I would say this is aimed at beginners / beginners plus. Whilst you can probably get away without having used a sewing machine before, it will be useful if you have a little bit of experience. Then you can get the best out of the guidance in the book.

There are clothing projects as you can see from the contents. On closer inspection, these are designed to be unisex and as low waste as possible. Or at least that is what I assume as a lot of them are based on rectangles. Stylistically they are not all run of the mill basics and I actually do like some of the patchwork that Wendy made – her style is strong enough to be recognisable and runs consistently across all her books, IG feed etc.

More interesting to me in the book is the out of the box thinking on the non clothing projects, whether it’s textile art of home accessories. When I think of scrap busting I typically think of quilting, bags, patchwork clothing. But actually, I could also make scrappy pillows, wall art, cards … and this would be a nice way to be a bit crafty without constantly making clothes.

Clarity of instructions and writing

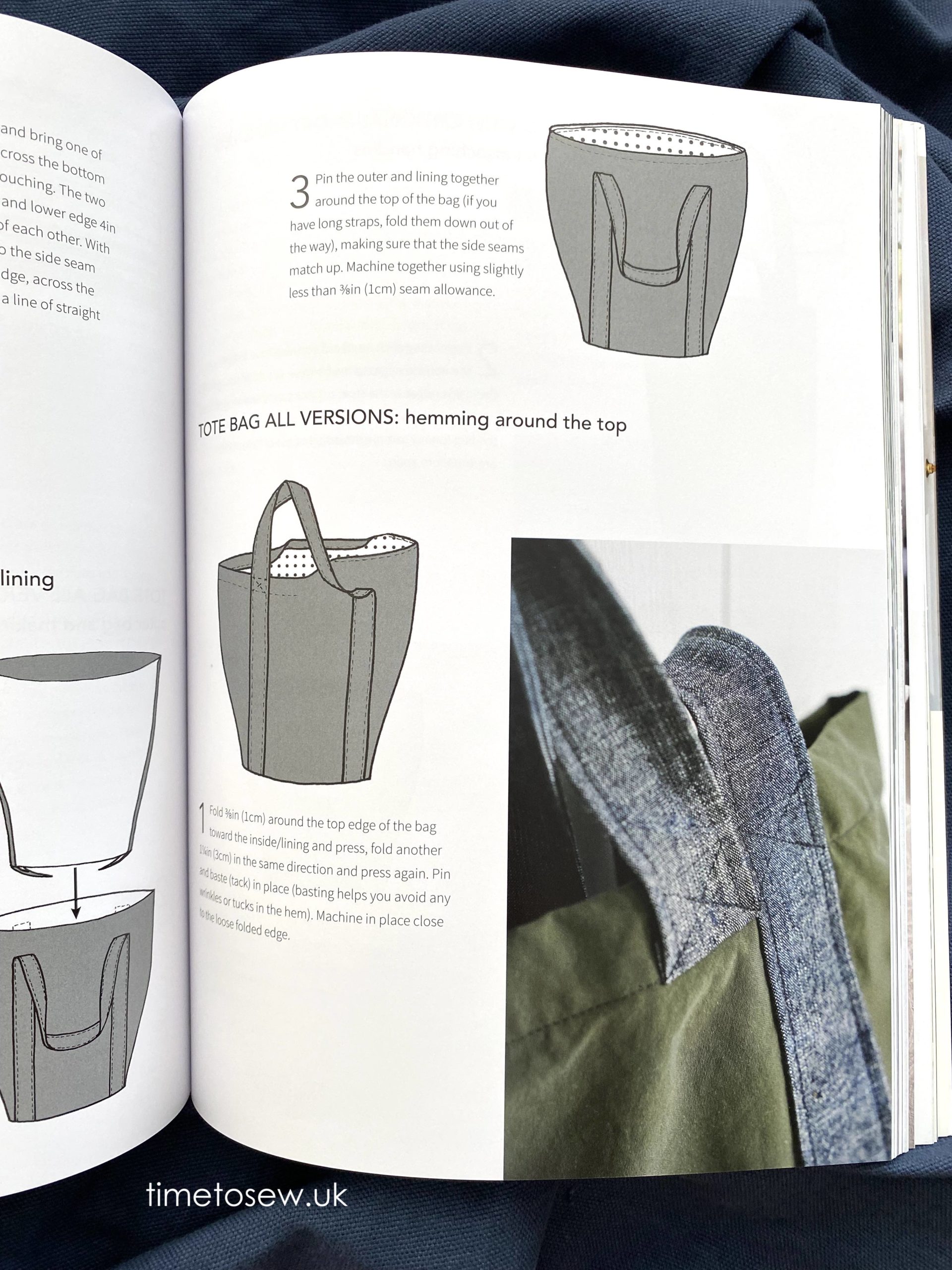

The illustrations in the book have a bit of an organic / hand drawn look and feel. But it’s easy enough to see what’s going on. For example:

As it is a book and not individual patterns, you will find yourself flipping backwards and forwards to find the instructions for drawing the pattern, construction etc. I found this a bit of a pain to be honest. But, this is the case for any sewing book I’ve ever come across. Apart from that, they were clear and easy to follow.

Zip pouch test

To fully test out the instructions on the projects, I decided to follow one for a zip pouch as I needed a gift for a friend anyway. It turned out well with no problems.

Dressmaking patterns

The Yes You Can Jacket, Robe and Top caught my eye so I thought to read through the section. It requires a little thinking – you have to draw the pieces yourself and take measurements that are not just bust/waist/hip. The instructions on where to measure are pictured, and where to draw/cut the fabric is also clear from the diagrams and the accompanying text.

It might be a nice exercise if you’ve ever wanted to have a go at pattern drafting but don’t know where to start. Or you don’t fancy buying a full on patternmaking book, making a block then adjusting. It is a bit more involved than following a ready made pattern, but not intimidating. I can’t imagine a robe would give too many fit issues so probably nothing to worry about there.

Verdict

The retail price is less than 15GBP. This is a very good price for the info and projects that you get (as you can see from the contents section above)! But, it also depends on whether Wendy’s style speaks to you. There’s no use in buying books etc. if the projects don’t appeal to you. My take on it:

This book is for you if …

- You want to have ideas for different things to do with your scraps

- You like spending time puzzling together your scraps and thinking about what colours and textures might go together

- You like patchwork clothing

- You enjoy home textile accessories that might be a bit quirky and different.

- If you need a gift for someone who is into upcycling and reusing

This book is not for you if …

- You only want dressmaking patterns

- You don’t like scrappy stuff

- You don’t want to go to the effort of drawing your own paper patterns

- You want straightforward fast sewing that doesn’t require any thinking (ie just follow instructions blindly and off you go).

Hope that helps in the decision making! You can buy the book from Wendy’s website here (no affiliate link)

Till next time

Kate x