If you read the news, you’ll probably have heard the noise about microplastics and plastics (even if its not as big a deal in the news as Brexit) in the last year or two. But beyond the scary stories and the big numbers that sound terrible, what do we actually need to know and think about? My long two cents on it is just the tip of the iceberg but in this post I’m aiming to give big picture view of the situation. As usual, I’m starting with definitions:

Microplastic: widely used to refer to particles of plastic <5mm long. They can either be manufactured (e.g. microbeads as exfoliants) or secondary (when bigger pieces of plastics break up). Current concerns are related to the amount of plastic that ends up in the ocean.

Microfibre: a type of microplastic. Refers to both

1) Individual fibres: including those that are shed from clothes when there is friction from rough and tumble in the washing machine.

2) Microfibre fabric: fabric made from the individual fibres being stuck together. You’ll know this from cleaning cloths that are meant to be more effective than your average cotton rag. Ultimately its plastic even if you don’t associate it with items like cling film or supermarket shopping bags.

The thing with plastic is that it hangs around forever and never fully disappears. This is because it photodegrades – i.e. breaks up, rather than biodegrades – i.e. breaks down like something you can compost. All plastic left in the open will turn into microplastic eventually from exposure to the elements. Even if it takes a

Plastics and oceans

Bits of plastics end up in the ocean due to littering, trash being blown away, and in the water via our drainpipes. There’s been a huge amount of interest in it in the past year or two (David Attenborough’s Blue Planet no doubt had something to do with it). But the statistics can be confusing due to

- About 8 million metric tons of plastic are thrown into the ocean annually. (source: Earth Day 2018 factsheet based on a study by Jenna Jambeck from the Univerity of Georgia published in February 2015 by Science Magazine).

- Some 18 billion pounds (

equivalent of 9 million tons) of plastic waste flows into the oceans every year from coastal regions (source: National Geographic article published Dec 2018. No study quoted, only that it came from Jenna Jambeck). - Between 4.8 and 12.7 million tonnes of plastic enter the ocean each year (source: British Natural History

museum website via figures published in the journal Science in 2015).

The source in stat 1 is the same as stat 3, but one says “thrown” into the ocean and the other uses “enter” the ocean. You could say its semantics – but regardless of what number you want to use, the point is that they all sound like

What about microplastics?

One stat I found said that each year, 5 million to 13 million tonnes of plastic ends up in the sea … it is estimated that the oceans contain 93,000–236,000 tonnes of microplastic particles, equivalent to 1% of global plastic waste to enter the ocean. (source: Nature.com, December 2015)

How much

We worry about human (and animal) health

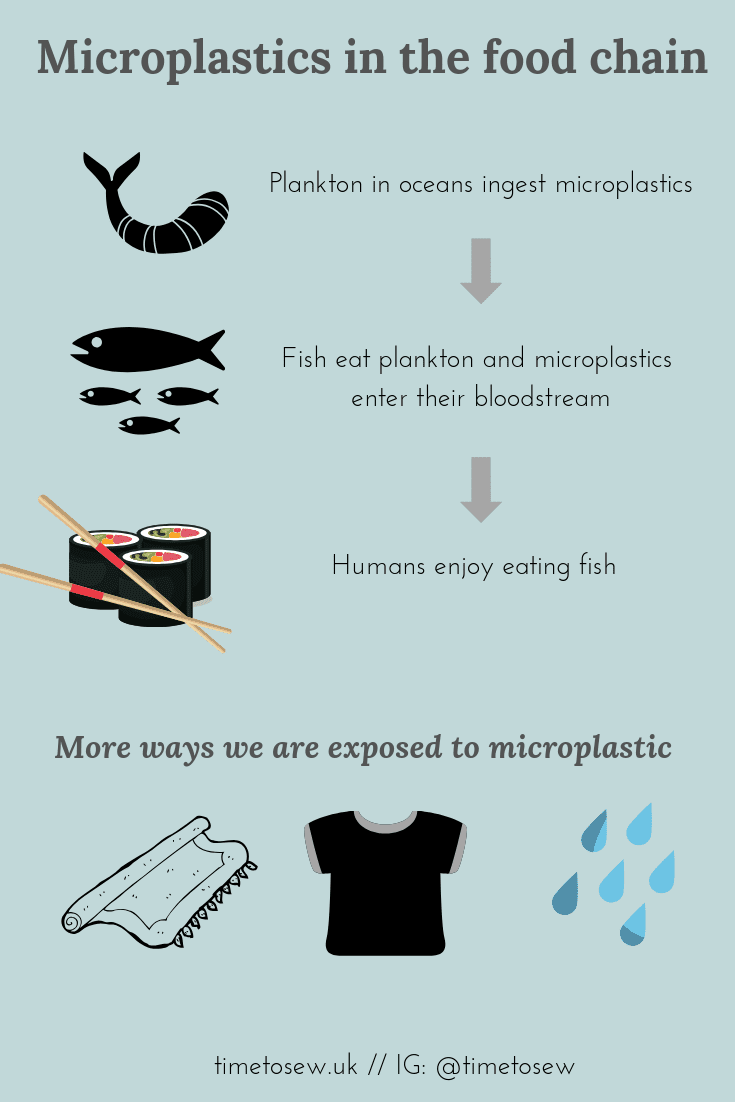

As time has passed we have discovered that microplastics are everywhere. They are in our food chain, in the water, in synthetic textiles, in city dust – even vehicle tyres shed them. And early (limited) experiments have also found them in us!

How did it get this bad?! It is worth remembering that this is a relatively “new” problem that has come into focus. Do you remember microbeads? The scrubby bits that used to be in exfoliants in the 1990s that guaranteed smooth silky legs – these were only banned in the US as recently in 2015! (not sure why pumice wasn’t good enough; I’d hazard a guess it is cost related).

What are you telling me, my seafood dish has microplastics?!

Well, its possible. But for now the news on eating seafood isn’t entirely dire:

According to the current state of knowledge on

– UN FAO, 2017toxicity of microplastics, the risk associated with the consumption of fishery and aquaculture products contaminated with microplastics is negligible and their benefits are known to be numerous.

From everyone I’ve spoken to and everything I’ve read, there is no black and white recommendation (yet?) to stop eating fish or seafood. Whatever you think about the grossness of eating plastic in food or in drinking water, I’m not sure there is a huge amount you can do to get away from it.

What there does seem to be is early days of research and lots of “potential” for things to be bad. The FAO in the article where I took the quote goes on to say that there should be preventative and corrective measures taken at all levels to evaluate the toxicity of plastics and find alternatives to plastic, reduce use etc.

What about clothes?

Synthetic clothes are the elephant in the room I haven’t touched on yet. The headline bad news is that that washing machines and water treatment plants don’t capture the microplastics that are shed by clothes – they are just too small.

The microplastics episode (March 2018) from the highly enjoyable BBC podcast “Costing the Earth” had some interesting findings to report. They interviewed Professor Richard Thompson from the University of Plymouth, whose study on microplastics has been quoted pretty widely. Here’s one such Guardian article here. According to Richard:

- 700,000 fibres may be released in a single wash in a domestic machine if you put in all the same types of garment

- Acrylics (think knitwear and non-wool yarn sold in craft shops) shed 4-5 times more than polycotton

- Polyester sheds 1.5 times more than polycotton

- He couldn’t confirm whether it was the fibre type or the type of weave that caused the differences in shedding

Microplastics aren’t just from synthetic fibres

A recent article in trade magazine Ecotextile News reported on a study which found more natural fibre (cotton and linen) and cellulosic (viscose and lyocell) microfibres in the deep seas of Southern Europe than synthetics. I’m not sure how this works with the biodegradability argument for natural fibres and the article didn’t specify.

The full version of the article int he magazine concluded that more research is required, but I have a niggling feeling that we’re going to find the microfibre problem isn’t limited to synthetics. PS – you can read my naturals vs synthetic blog here.

What do I do now?

Well, like so many sustainability-related issues the big-hitting solutions are slow in arriving. Interested citizens are taking matters into their own hands and there are small businesses out there trying to innovate. By now, there are lots of articles out there with ideas for reducing the potential impact of microplastics, as well as products being invented to help individuals. Here are a few links, but if you just google you’ll find loads more:

- 10 simple tips – article

- Washing article – BBC News

- Guppyfriend bag – sold in lots of places now

- Cora ball for washing – not tried it myself but these user reviews were a bit off-putting.

Unfortunately, there’s probably not much you can do about food, water and ingesting microplastics in everyday life. All the research so far points to the need for more research and bigger impact solutions. But it’s better to know about these things and talk about it, right? My theory is the more the public knows the more push there will be for solutions right.

I hope this article has been a useful read or

PIN FOR LATER:

3 comments

How scary it is that so much of it is going into the waterways and ocean. And then up the food chain back to us (although at negligible levels, but they are there!). The ocean is so vast and most people don’t realise just how much pollution we are creating. It’s always nice when I see companies and businesses adopting more environmentally friendly practices. Even just paper straws and wrappers and wooden/bamboo cutlery instead of plastic. And we can of course do our bit too! Thanks for the very informative and interesting read Kate!

Thanks to you Sil for the ongoing support. Yeah it is an incredible amount of plastic that is getting into the oceans, but can you imagine how much waste is being created generally, if this is just the plastic litter? All adds up I guess. On the cutlery thing – I have a portable set that I take everywhere, but in shops sometimes I now see paper straws and plastic cutlery side by side (insert eye roll). Better than all plastic I guess, but it just tells you that the shops don’t care *that* much except to react to public outcry over straws.

I admit I haven’t yet followed the link, but I don’t see how linen and cotton can be a source of microplastics or, given your definition of microfibres, of microfibres, either. That’s not to say they aren’t a source of microscopic fibres or that they aren’t as much or more of a problem. But they can’t be a source of specifically *plastic* pollution. (I’m not sure about viscose and rayon. Do they count as plastics?)