Deadstock. Over the last couple of years, I have heard a lot of people talking about buying deadstock (or overstock) as their method of incorporating sustainability into their sewing. The reasoning behind it is usually along the lines that the fabric would otherwise have gone to landfill. But how big a problem really is landfill, or in other words, how dead is deadstock?

A quick reminder:

Deadstock / overstock is the unwanted fabric from milled fabric (i.e. a specific fabric that has been commissioned by someone). For example, this could include leftovers because of over ordering, fabric being unwanted due to colouring being incorrect, or there are printing errors. You’ll often see this in independent sewing shops being labelled as “ex designer” and it can be quite inexpensive.

Last year I wrote about the sustainability case for using deadstock, you can read that here. For me, deadstock is a sustainability yay in one sense as it isn’t milled fabric, but I don’t see it as being the be-all and end-all solution to sewing sustainably. There are a couple of things I think worth highlighting that make a simple “fabric in landfill” line a bit problematic.

Is deadstock actually destined for landfill?

The generic phraseology thrown about in terms of things “going into landfill” can be just misleading. For example, in the UK, 85% of waste is incinerated, not landfilled (see my post here about landfill). Perhaps it is semantics, but it irks me that landfill is used to conjure up this powerful image of piles and piles of textiles being dumped and this is what captures public imagination. The statistic I found for Bangladesh from a UN report dated 2017 is that textile waste forms on average 3.06% of all landfill in cities – less problematic than food and veg waste at 68.69%.

In some ways I guess this is not so different from the Burberry incineration incident that also made all the media headlines a year ago (they announced 3 months later that they would stop destroying unsold stock – assume the reputational damage was more than what the unsold stock was worth). Whilst we know that many brands share the same practice in terms of destroying stuff for brand protection purposes, Burberry was singled out because it was transparent about it…. which kind of makes it a no-win.

What happens to leftovers in big factories?

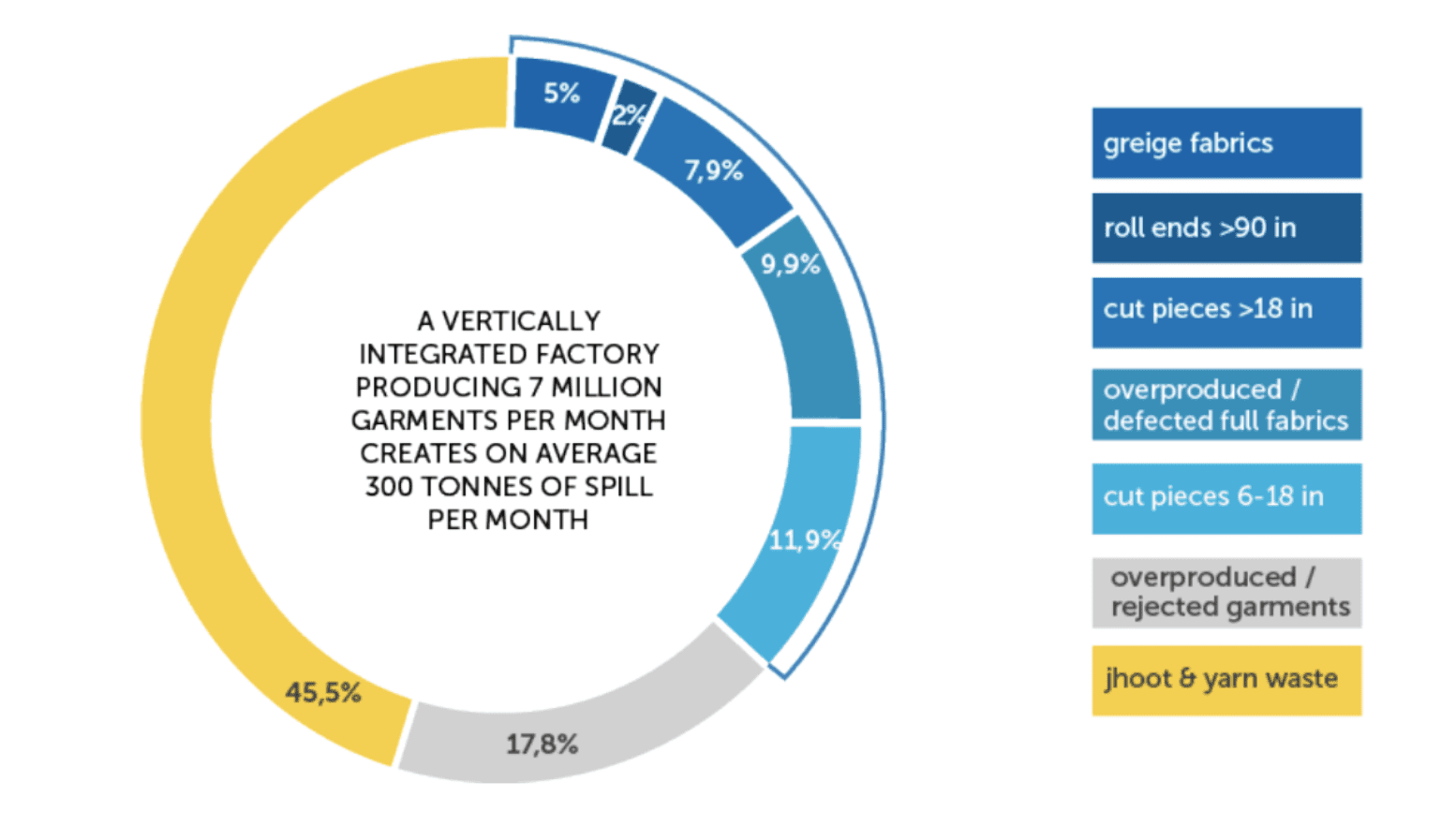

In looking at deadstock I decided to read the Reverse Resources white paper again (dated October 2017). Whilst there is dumping of unwanted fabric going on, the paper also includes a graphic depicting a model of the types and proportions of spillage from big vertically integrated fabric and garment production factories. This shows that only 2% of spillage is end of rolls (>90in), and 9.9% overproduced/defected full fabrics. Which is really small compared to the sum of jhoot and yarn waste and overproduced/rejected garments. Interesting right? Suddenly the deadstock issue doesn’t feel like the biggest waste problem around (for factories anyway).

The authors also point out later on in the paper that selling the leftovers is actually an important source of revenue for factories, particularly as the margins on garment production are so low. Because of this, there is little incentive for them to be transparent about waste and there isn’t too much transparency in the secondary market. If we apply this thinking further along the chain that also implies that we probably aren’t going to have too much luck with knowing what we are buying or where it comes from. So as a consumer it becomes even more convenient to think that fabric is just unwanted, and move on.

Deadstock doesn’t solve the consumer culture problem.

In the last couple of years I have talked extensively about consumer behaviour and how we are encouraged to buy more all the time – see here for some opinions on a symptom coined “affluenza”. And I get it, I love buying stuff too! And sewing new stuff! Who doesn’t like new and shiny things? Especially an inexpensive “ex-designer” deadstock fabric that makes us feel like we’ve scored a massive bargain?

It is convenient that deadstock can be marketed as a sustainable product just because the reason for selling is that it is not fit for purpose. No different from any second-hand product really except that the material is still virgin. Indeed, the contradiction of all sustainable fashion related sales is that no one in their right mind will ever say don’t buy – we just say buy better if you are going to buy.

If you want more on why deadstock isn’t as good as it sounds on the surface, here’s an extract from an article from an industry insider:

Dyeing, knitting, weaving, and printing require huge, complex machines. Some ranges can take up entire city blocks, and take multiple people to operate. It takes a lot of man power to turn off the machines, clean them, set them up for the next fabric, and then run a new fabric. It is cheaper for mills to produce extra fabric that they plan to sell at a discount than to shut the machines off after the order is fulfilled.

This means that in their basic costing, mills plan to sell x percent at full price and y percent at a discounted deadstock price. At no point are they calculating a percent going to the landfill. Remember mills are in the business of making money, not wasting it.

Melanie Di Salvo, Shop Virtue and Vice

Deadstock is just one way of sewing sustainably

At this point I’m reminded by something that Clare Press (Sustainability editor for Vogue) said to me when I interviewed her:

One of the secrets to make fashion circular or sustainable is recognising that different kinds of consumers are looking for different things.

– Clare Press, author of the books Rise and Resist and Wardrobe Crisis

Committed upcyclers probably buy something every now and again from a thrift shop. Other sewists spend time in fabric stores. Some might be looking for designer prints, others might look for deadstock. The point is that we all buy stuff and we all have different attitudes towards buying, sewing and sustainability.

I’m not suggesting that buying deadstock is a poor way to try and be sustainable about sewing – nor is it the only thing that can be done in the name of sustainability. I’m just keen for us to remember that there are shades of grey with most things fashion and fabric related and that there is more to think about beyond simple statements along the lines of “deadstock would have gone to landfill anyway”. And on that note, I’ll leave it to you to decide whether deadstock is actually dead!

PIN FOR LATER:

7 comments

Oh, only 2% of factory textile waste is deadstock fabric? Makes sense,but it’s less than I thought though. I’m also looking at the the 6-18inches scraps making 12% of waste. I produce mainly those in home sewing 🙁 . If only every factory/company has a quilting department and use up all those scraps too (large percentage if adding other scrap sizes)…

At the end of the day I think it’s all commercial. The good news is that there are organisations that are actively looking at what to do with the scrap – but there needs to be some kind of incentive for the factory to report accurately! Luckily at home you are in control of a lot more….

Once again you give us a thoughtful, data based article. Always provides me with several ideas to think about. Thank you.

Hi Ellen, glad you enjoy reading my blog and that it’s useful to you! Thank you for the feedback, much appreciated

Another thing to consider is that if you are a home sewist then likely much of the fabric you buy will be dead stock but not labelled as such. In my experience it is very common practice for fashion labels to commission exclusive fabrics/prints, store the excess at the factory for a season then sell on to local fabric markets in China, India etc. Retail fabric stores or wholesalers then buy the fabric lots from the markets and sell on. I’m very saddened by the waste at the top end of the market but glad that much of it does find another use either with smaller fashion brands or home sewing instead of landfill/destruction. As sewists we need to understand that in the fast world of fashion fabric production we are the ambulance at the bottom of the cliff but we can do our best to give the unwanted and onsold waste a forever home.

Hi Jacqui, thanks for your comment. Regarding common practices – this is exactly what bothers me about the “it would have gone to landfill anyway” type of line. And whilst the use of deadstock might work for the smaller fashion brands and home sewists, it doesn’t solve the fast-fashion issue (especially if we think about why deadstock exists in the first place). Having said that, what will solve fast fashion? A multipronged approach and I’d suggest a whole lot of less! I try not to be too glum about these things, else I might get eco-anxiety and lose hope.

Im with you there!!